I Must Change My Life (part 1)

On re-reading Mrs. Dalloway & conversion experiences & the art that forms us

…when the sentence was finished something had happened. —Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

I encountered a few surprising things while I was trying to write down my thoughts here. First, I was for my Woolf bookclub re-reading A Room of One’s Own, an essay I had last read very ungenerously and without any understanding when I was an undergraduate but which this time led me to a whole bunch of thoughts about what we call the “craft” of writing. Second, a friend sent me a paper by Daniela Dover on what Dover calls “erotic curiosity”— love, curiosity, attention, and also Mrs. Dalloway1. I will try to talk about some of this in the next installment.

Mrs. Dalloway Take One (this book has changed my life!)

Years ago, a friend and I were discussing the art that had changed us, and wondering whether it only could when you were young. Some works of art are formative, we say. Some relationships are, too. In your youth you have an openness of mind, a spongey-ness of self, and can you cultivate this in a self once she has gone through decades of real living?

Since I am an optimist, and a romantic, and, unfortunately, a strong will, I refuse to believe that you cannot be affected as you were when you were, say, 16 and 17, years when several books blew my mind and changed it; when you were 23, the age I was when, nearly two years married, I watched Before Sunset and decided I no longer believed in marriage2; when you were 25, even, the age I was when I read Mrs. Dalloway and then dropped out of my PhD in English Lit and burned as many bridges as I could on the way out.

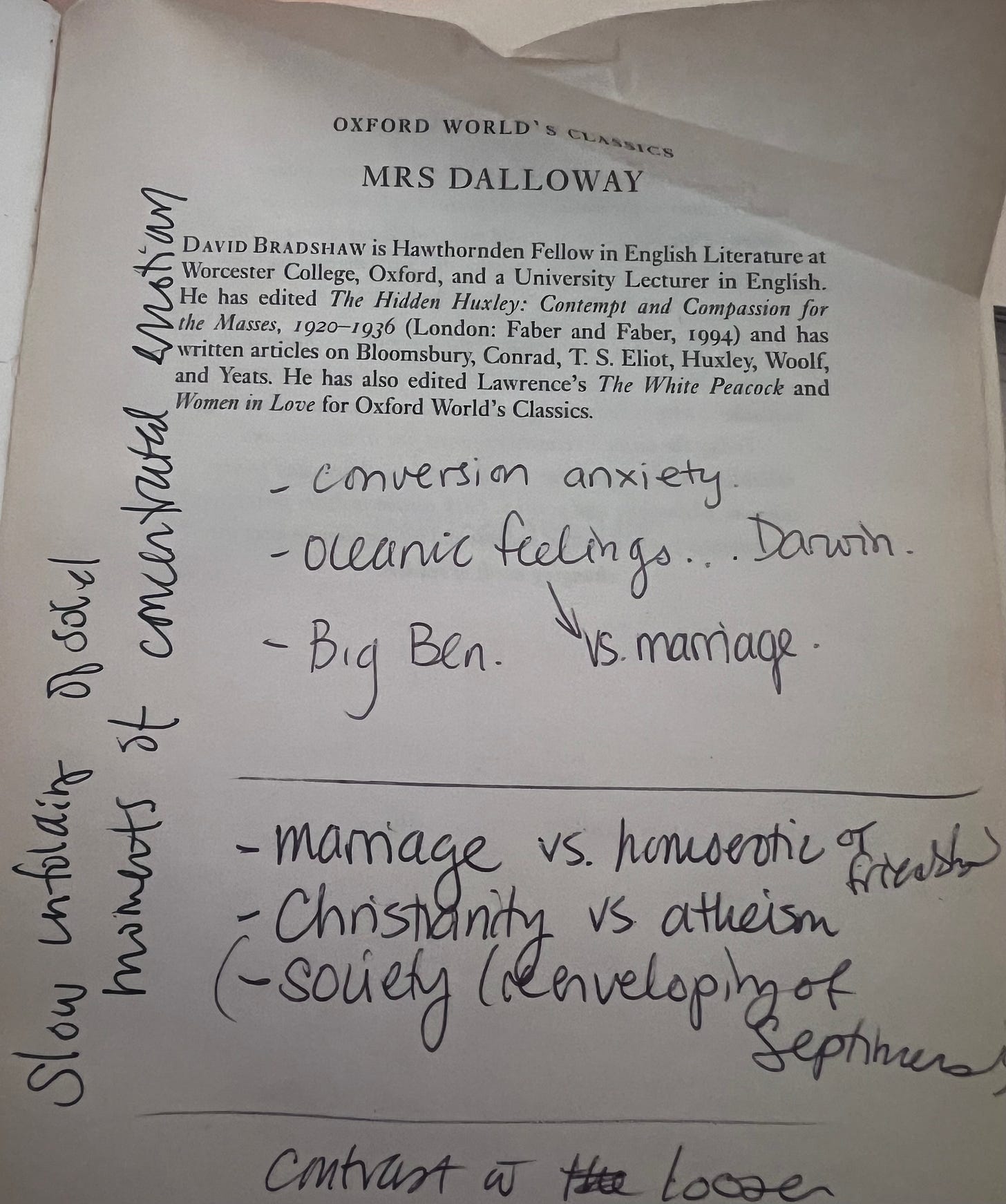

I was reading Dalloway for a class I loved during that first semester of my PhD. I had gone through a de-conversion experience or two already—after multiple conversions-to-Christianity in my childhood and early adulthood because I kept hoping that one of these would finally, actually stick, and change me—and had hoped I might be able to write a dissertation on conversion narratives, but also I was unsuited to academic work: passionate about things, but, like Simon Peter, easily wooed to forget that passion. Easily converted, easily de-converted.

I read Dalloway quickly, almost in a single day. I read on the long bus commute I took from Hamilton all the way to York University, in the very north end of Toronto, gobbling it up like a page-turner. I was nearing the end when I stopped at the campus coffeeshop for breakfast; sitting on a bench near my classroom, I read the final page.

I described the experience of reading those final lines as feeling the ghost of Virginia Woolf breathing on my neck3. The ghost of someone.

“I will come,” said Peter, but he sat on for a moment. What is this terror? what is this ecstasy? he thought to himself. What is it that fills me with extraordinary excitement?

It is Clarissa, he said.

For there she was.

Nearly 100 years after Mrs. Dalloway was published, I sat on a bench and felt chills all over my body. What is this terror, what is this ecstasy. What was it? Something had happened to me beyond what was intellectual, and beyond what was emotional. It was, I concluded, so spiritual I could not put words to it.

Yes, I saw the light. I could find no way to talk about this moment in my class, where I instead presented a paper on the words “Proportion” and “Conversion” in the middle of the text. I saw that I would not go on trying to analyze books and find new angles on old books or pore through archives to find a gap no one had before in order to get the SSHRC-funding one would need if one had any hope of getting a job: I would devote myself to my real love, which the cold breath of Woolf’s ghost had recalled to me, the way a man might call someone to leave behind his livelihood as a fisherman in favor of the uncertainty of discipleship. I would devote myself to writing.

Briefly: On Conversions, here in the middle

I have far too many disparate thoughts I’ve amassed over these years of not having written that dissertation on conversion narratives, which grew to include the question of the transformative experience, which was how I experienced motherhood. But I will offer a caveat to undo the little tale I just offered: conversion narratives, like the testimonies one gives at church, are performative and selective.

Mrs. Dalloway really did have this mystical effect on me, but maybe it is not really a story of a changed person but rather a story about how art can affect us along the nerve endings, bypassing the intellect, and how this is worth devoting oneself to. But this was no Road-to-Damascus conversion. There were about ten other things going on that year that caused me to leave academia in favor of art, many of them far more reasoned and less sudden.

After divorce—I am speaking of my own experience of the way it shatters the self as well as the experiences of myself and others who discover a stranger in the place of a person who was once intimate and beloved—it is easy to look at people in wonderment at how they’ve changed. But I don’t feel changed by divorce, exactly; I feel that something in me, always there, has been revealed.

What might it mean to change, to learn from one’s epiphanies, to take the humblings one has been dealt and be transformed?

Mrs. Dalloway Take Two (Love, Attention, Mystery)

When you give a book this kind of formative power it is a bit scary to return to it. What if the magic was dulled? Reading it had been a private memory of an ecstasy I’d once felt, and when people asked me my favorite book, Mrs. Dalloway, which I’d read only once all the way through4, was my answer.

I had felt the pain of finding a beloved work of art changed because I’d changed when I re-watched Magnolia some twenty years after seeing it at the end of high school. So moved was I then by the Catholic cop John C. Reilly character’s bumbling plight as he begs God in the rain to help him find the gun he’s lost that I would cry a little even to recall the scene days later. I bought the soundtrack; I bought the two-cassette VHS and carried it from apartment to apartment to house to apartment without rewatching.

Decades later, finally watching it again, it wasn’t that I wasn’t at all moved by the film, but of course I was moved by different things. And this character I had felt so much for left me cold. It lost some of its luster in this translation across time. I had, rather obviously, changed.

The week I spent re-reading Dalloway, my life was different in every way from the one I was in when I first read it. But the novel did have a strange effect on me, again. That week, the moments of my everyday life seemed overfilling with richness and abundance and light. I have had these experiences, too, watching Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson, Wim Wenders’s Perfect Days, and work by Agnès Varda. That life is delightful—plentiful—beautiful?—not only because at any moment something could happen or someone could come along and change absolutely everything but also because so much is happening around us all the time.

I guess it’s about the mind. It’s about many kinds of love. It’s about how we experience time. It’s about attention. (Simone Weil: “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity”).

I felt, to rather dramatically paraphrase Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” that I would have been a good woman if this book had been there to talk to me every day of my life.

As I got to the final scene, at the party, when Septimus dies and Clarissa has her life-affirming revelation of connection to him and then disappears for several pages, I felt myself anticipating. What would happen to me when I re-read the final lines?

I was surprised that, again, I felt those bodily chills, that mystical feeling that something was expanding in me. But this time I did not think: ghost. And this time I was able to put words to it to myself, to understand what had happened. Something happens in the pages where, after her revelation, Clarissa disappears and we wait for her to re-appear. My bodily (spiritual?) response had to do with something I’ve been thinking through and chasing for all these years, the moment that feels mystical because it is a moment of the real peeking through the layers of nonsense and self-absorption and habit.

And on top of that, the feeling a work of art can give you, that something meaningful can be communicated by a woman long dead to a woman now living. And probably the feeling that a work of art that changed you when you were young will be a work you always love.

So perhaps I am still open enough. Perhaps I am still spongey. To be open is to risk being influenced or even hurt, badly, by others. Still, the struggle has been, I think, these last few years, not to change but to remain open and soft and silly and passionate. To remain myself.

A few related reading/writing recommendations

Any of my fellow Dalloway-freaks would be wise to acquire the incomparable Merve Emre’s The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway. She describes, in the introduction, retyping the entire novel herself, and I was (am) all envy.

Joseph Earl Thomas’s God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer is a novel of this year written in a stream-of-consciousness in a single day, and it offers some of the same pleasures that Dalloway does. Real acquaintance with a mind; real acquaintance with daily life. One of my favorite passages is one in which the narrator describes, in detail, lovingly cleaning someone else’s body:

“The pleasures of cleaning so thoroughly, so exactingly, someone who cannot do so for themselves. Really taking one’s time and getting into the crevices, the butt holes, under the balls and titties, underarms, back fat and fupas, tender flesh creases behind the kneecaps, inside the crusty ears and under the fingernails, between those emaciated flaps of flesh, into the sunken jowls and worn down shoulder pockets. Everything: I want it all.”

I loved this essay “The New Age Bible” by Sheila Heti in the latest Harper’s about the strange book A Course in Miracles. She talks about the feeling of mysticism one can have while writing, among many other fascinating things.

And, finally: one of the members of my Woolf pack sent us a link to this substack from George Saunders,

which led me to this interview with Ursula K. Le Guin talking about Virginia Woolf and finding the rhythm in your prose.

And this has, unfortunately, brought me to a whole other set of thoughts I have about romantic love which I shall resist getting into here! This is not a book I’m writing right now! But there will be a part 2, I fear.

One of my favorite parts of this memory is how I told a friend that I’d watched Before Sunset and it had made me stop believing in marriage and she said, so quickly I thought it must be true, “that movie ruins a lot of marriages.” We were both, she and I, 23 at the time.

I do not believe in ghosts.

Not counting the near re-reads to write the essay and not counting the romantic (to me) phase of my marriage during which I read paragraphs of it to my husband aloud.

I’m so loving immersing in your thoughts. Thank you. x