CN: brief mentions of childbirth, postpartum depression, sexual assault, Harlow’s monkey experiments, Alice Munro news

Cult of Natural Motherhood

When my children were very young, I was prone to joining cults. I use the word “cults” loosely, and what I mean is that I was very vulnerable to answers to the only question I was asking: how is one supposed to live? In my mid-twenties, living with uncertainty in every direction, responsible for young lives, I felt that I went through every day asking the question. Maybe it was more like how am I supposed to live? A religious question, and I was still religious then, but I was already partway into the long process of losing my faith and was married to—and deeply in love with—an atheist.

I could track the devotion I felt to certain answers to this question with each child. With my oldest, I was shocked epiphanically by the love I felt for her and thought that meant I should devote myself to motherhood, and I did so with gusto, turning to what we called “natural mothering,” joining La Leche League, and trying to model myself after one particular blogger who was homeschooling her five children and knitting things from hand-dyed, hand-spun wool she’d sheared from animals on her hobby farm. By the time I had my second child, though, 22 months after the first, I was hit with the question again—how to live—because I was also walloped with postpartum depression. I realized I needed feminism again, the new epiphany rewriting the old one, which, when I had my third child and another life-changing epiphany, I discovered was a process that might never end. (My favorite quote from literature had long been from Virginia Woolf’s Orlando: “I am losing my illusions, she thought, taking her taper. Perhaps to acquire new ones.”)

It was around that time that I made friends with a woman from La Leche League. Her influence on me was strong, because her certainty was also strong. A yoga teacher, a raw vegan1, a person who once stopped me talking when I was telling her about a book I’d just read but which was really dark—

—to tell me that she wouldn’t read something like this or any world news of any kind because knowing too much about misery would only add to the misery of the world. This comment woke me up, when I was already having my doubts about the cult of natural motherhood, because it went against the principles I held more deeply and would never give up. That one should not choose, in the way of Millet’s mad narrator, to spin terrible things as good things. That one ought to try to tell oneself the truth. That the only way to avoid falling into the void was to stare into it? Without flinching? That, in fact, if I was going to be a writer, this was kind of my whole job?

But also I was in a genuinely miserable state, deep in that postpartum depression, just trying to get through the days. She told me that whenever I felt like that the best thing to do was “legs up the wall pose,” where you just lie on your back and put your legs straight up a wall.

This advice seemed so silly to me and to my husband that for years we had a little joke about it—anytime something awful happened we would say to each other “hey, why don’t you just put your legs up the wall?”

My Toes on the Wall

One thing you lose when you lose a person—in my case, via a wrenching break up and eventual divorce—is that whole catalogue of inside jokes.

My second birth was extremely difficult, and a life lesson, too, since I insisted on not using anything for the pain and emerged from it at first triumphant and soon realizing that maybe if I’d been a bit less unrelenting, shall we call it, I might have had a restful birth that didn’t set me up for such a bad emotional outcome. (Maybe the cult was wrong?) Afterwards, my doula told me that she’d never been at a birth like that, that even during the worst part of it, when I was attached to multiple wires and machines, and they were having to hold me up so I could do lunges, and I was falling asleep in the 30 seconds between contractions, Adam and I were making jokes and laughing.

A year into the breakup of this marriage, my father told me, “well, one thing about you, Liz, is you can find the joke in any situation.” I was delighted by this view of me, one I hadn’t known he’d observed, and when I looked into it later I found that being able to joke about the really bad things that happen to us can be a coping response. A new friend told me his favorite thing about me was how I could laugh at myself.

By then, I had been so humbled by heartbreak I tried absolutely everything just to feel better for a few minutes at a time. I had to learn something I’d never learned: I had to learn how to cope. I didn’t and couldn’t wallow, since I was also facing the enormous logistical and material challenges of dismantling the kingdom of our marriage, but I was not proud. I wrote down a list of things I needed to repeat to myself when I woke up in the morning, like today you will be the most gracious and beautiful version of yourself. Today you will remain soft and open. I extended this grace to myself: when I failed—sending, say, a series of angry texts to Adam—I told myself you didn’t like how that felt, so you will not do that tomorrow. I went for long walks. I called my friends and asked for help. I went to a sound bath. I got my Tarot read. I fell to tears in public. I wrote poems. I became addicted to nicotine. And I started doing a lot of yoga.

And so it was that I found myself lying on my mat on the floor after a grueling yoga session, all the feelings wrung happily out of me, my feet flat against the wall. I stared at my toenails, hot pink from a pedicure someone I was dating had paid for as a birthday gift, then wiggling those toes, thinking how lovely it is to have toes and thinking how lovely to have a body and thinking this is my body, the body of my beloved, since the effect yoga had on me was to turn me briefly into to my own beloved, my own little baby, my own sweetheart, and I remembered the pose that friend had suggested to me all those years ago.

The joke was, as always, on me.

But the void

When my kids were babies and I was trying also to become a writer—those were often very dark years. Some pain somewhere deep in my body was triggered, something mysterious to me and to do with my family of origin. I wrote a short story around then that I described later as a weird little miracle. I sat down to write and blacked out for the duration of the writing, then emerged from this trance with the best story I’d yet written.2 It was about a single mother whose teenaged daughter is having a mental health crisis—yes, it was based on my life—and at the end of the story the mother holds the daughter thinking, but I don’t know how to love. No one ever taught me how to love.

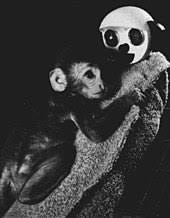

I was delighted to have written a story in a trance, to have channeled something, but also writing it seemed to have unsettled me in some frightening way. We tried that night to watch a movie, but the movie had a rape scene I couldn’t bear to watch, and I couldn’t sleep at all that night, felt a familiar bodily sensation I often felt during such insomnias and which I called, to myself, since I was a child, because I cannot convey what this feels like in words, the marshmallow feeling. The kind of unsettled I felt was triggered in a similar way by the Harlow monkey experiments; once, trying to watch a documentary about these experiments, I had such a bad physical reaction that Adam remarked on it with alarm.

I knew all of it had something to do with mothers and failures of mothers and the awful distortions that can occur between mothers and their children. In fact, during many of those years, I would become annoyed reading work by people grappling with the difficulty of motherhood, since they were so far from expressing what felt like the true horror of existence it seemed to me a lie.

Maybe it would have been nice if I could have afforded psychoanalysis.

So when the Alice Munro news came out this weekend3, more than two years into my efforts at healing, my attempts at starting over, my realization that I might be a better mother now that I’m divorced, something was triggered in me that had me lost for a few days. Global crises and personal events had already been sources of anguish for many months, but I was filled with a visceral rage about what Munro had done, and not because she is particularly dear to me as a writer—though I’d had a harrowing experience reading Runaway several years ago, another set of stories about motherhood and pain—but merely because of the facts of it, because of the evil of it.

And then I couldn’t sleep. And then I was angry, again, about the Abandoning Mothers chapter in Claire Dederer’s book on the art of monstrous people,4 and then I felt helpless and scared.

I was trying to be a writer and I was also trying to be emotionally healthy, good to my loved ones, a person of courage and grace and mercy. And I also believed that my sensitivity was what made it possible for me to be an artist; or: that I had to be an artist to make something meaningful of this sensitivity.

If art is my cult, my god, where does that leave my relationships? Because does being a writer mean having to really face what is most awful in the world? Does being a writer mean having to go through all this as I romantically believed as a young person? As I still believe? Didn’t writing make me better? What if being a writer wasn’t, as I’d told myself for years, the only good thing about me? What if it isn’t the thing that has redeemed me or anyone? Can I put my legs up the wall and solve that? Where is the joke here? How will I sleep?

I spent a week trying to turn us into raw vegans until I realized this was a project only available to people with money and spare time.

I still think this may be true, and though the story turned out to be important to my career it was never published.

You can google it. I don’t want to say more.

I’ve already written too long an essay. What’s the matter with me. More on this some other time.

What if artists will never have any answers and we can only ever try to find better questions? What if the seeking is itself the grace? In other words, I miss you ❤️