On marriage or maybe against it

Where I can't even commit to having an opinion; also: reading Eve Babitz & Emily Witt

[Adam Phillips] asks “what a person’s life might be like if they were unfrightened of their own complexity, or refused to determinedly narrow their minds, or were unintimidated by their unbidden curiosity.”

—quoted by Jessa Crispin

I am feeling a bit opinion-avoidant lately, at least in any public space, since there have been costs to my relationships in this past year as far as social media and political ideas have gone, and I am trying to write about these things the only way I know how—in a long-simmering and novelistic way1. However, I do know that many of my thoughts about marriage and divorce and heteropessimism and feminism converge with some of those political opinions, and I guess that’s might be the theme of this late-coming substack, which I haven’t been able to get to because I’ve absolutely exhausted myself trying to cobble together gigs for pay, getting ready to go back to school for retraining, and trying otherwise to do nourishing things like spending time with my friends and my children and reading a lot. Also, in my ongoing efforts to live unproductively in the midst of this highly productive living I am participating in little romances and just finished revising a 10 000 word story no one asked for and which I labored over for months!

But first, I’ve published a story about an open marriage

between exvangelicals called “Missionaries” at the Notre Dame Review. It is, I guess, also a story of our time, since the protagonist, a former social worker turned podcaster, has begun using dating apps during early COVID and she and her husband have lost their faith in Christianity (and God) post-first-Trump-round. You can read the whole story online (the print issue has an unfortunate misprint), but here’s a snippet:

She woke up in her own bed, wanting to teach Jeremy a lesson. She wanted to teach him all the old lessons she herself was trying to unlearn: about God, about love. Such as: sometimes grace should give you a thrashing. Such as: sometimes love could take you out at the knees. Jeremy believed that because she didn’t know what she wanted from him, that because she already had a husband, he could treat her however he wanted.

Jo and her husband have landed on polyamory as part of their attempt to “deconstruct” their faith. “Sex and love,” she thinks, “were the first thing every cult had to deal with. Feminism. The sixties. Fundamentalists.” Her own sister is a complementarian Christian who, in an act of Godly devotion, will not use birth control.

My thoughts about marriage could fill a book

and probably will. I also have a lot of opinions about polyamory as the solution to the ills of monogamy, which I will also hedge about here. But I will offer that even during my very long marriage to a man I loved and was devoted to, I suspected that being married didn’t suit me, even going so far as to propose divorce when we were only a few years in and still deeply in love with each other, since I thought I might feel less burdened by a situation in which we were just great lovers.

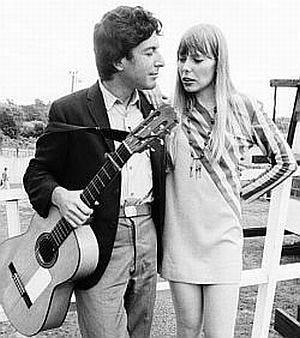

In my early twenties, how was I to know which life I wanted and which visions of life had influenced me? How was anyone? The greatest influence on me was, obviously, the extremely serious Christian subculture that had shaped nearly every aspect of my life since birth, a very pro-hetero-only-marriage culture where, when I was a teenager, elders in the community began to express concern that my intellectual “ambitions” and perhaps “ability” might get in the way of me marrying a “good Christian man”. But I had sought out other exemplars in the seams and was influenced nearly as deeply by images of Leonard Cohen in some austere apartment in Montreal smoking cigarettes and being a so-called ladies’ man. I had bohemian/artistic fantasies of freedom which were the opposite of the settled married person I became out of, perhaps ironically, an act of romantic recklessness when I was still an undergrad and madly in love.

How lucky I feel to have been madly in love when I was young enough not to doubt it! How lucky I feel to have lived with this love through its many other incarnations, to have had children young, even though all of this was extraordinarily difficult, to have grown up with someone who was in a relation with me of mutual respect and adoration. I was torn all the time while being married—I was always trying to get a glimpse of the ghost of the other person I might have been in my 20s—I used to quip that I was trapped in a happy marriage—and now that I’m not married anymore and have lived through the hell of catastrophic heartbreak—now I’m trying and probably failing to see it all clearly. To see what it all might have meant.

But, reading some of the divorce memoirs and novels that seem to have proliferated lately, I feel the difference between myself and many other former wives of my own demographic, and I will be trying to figure that out for a while: what it means to be part of historical trends and the desire to continue to believe in your own particularity and whether the other options, where you don’t get caught in some lifestyle groove someone else has prepared for you, are merely illusions to make you believe you are free.

Brief aside with links on the 4B movement, heteropessimism, etc

I have been reading about heteropessimism (and the problems with it) and marriage abolitionism quite a bit, and I’ll direct you to a couple writers who have more interesting and thought-out things to say about it than I do.

Jessa Crispin, whose podcast I now devotedly listen to, writes in her substack on this topic:

As Adam Phillips writes in Attention Seeking, curiosity about what else is possible is often experienced as a psychic threat. People kill off their curiosity and sense of possibility (outside of the consumerist experience of shopping for better products, of course) in order to survive without the underlying tow of regret and disappointment. He asks “what a person’s life might be like if they were unfrightened of their own complexity, or refused to determinedly narrow their minds, or were unintimidated by their unbidden curiosity.”

and I’ve also really been enjoying reading Tracy Clark-Flory's substack; here is a great interview with Sophie Lewis called “A feminist utopianism”. Here’s Lewis:

We allow people to have sole responsibility for the care of dependents—of children and also partners, who are expected to have all of their needs met by their partner or spouse. This is actually bonkers. It’s a backwards way of looking at things to say: “Who has the time for polyamory?” Who has the time for monogamy? How are you supposed to get all of your needs met in an isolated dyadic household? Our needs need to be met more collectively. I want to see a return of things like public or common kitchens, recreation spaces, maybe even laundries or pantries—things that recognize that nobody needs to be doing the same exact tasks over and over and over in their tiny little boxes at the end of a day.

The book discussion segment of this letter

Maybe when one goes through something like a divorce one is looking for one’s own experience reflected back as a way of getting an explanation for the thing that has passed through unrelentingly and with such a storm of factors it’s impossible to make sense of it. A novel might make sense of things. A memoir might. A film, even, like “A Marriage Story,” where an impasse about geography rang true.

But some of the novels/memoirs I’ve read recently that I found unsatisfying on this topic were Sarah Manguso’s Liars, Miranda July’s All Fours, and Leslie Jamison’s Splinters. Liars and Splinters annoyed me for some of the same reasons, to do with the way the narrators seemed to self-aggrandize or at least to make themselves into perfect victims of circumstance while remaining ideal mothers2, and Miranda July’s novel stuck with me in a bad way, since I loved it at first and then later felt somehow discomfited by it out of what might have been a bit of my own class resentment3.

On a morning after my marriage collapsed I found myself in the middle of a new, doomed relationship, and I lived out a perversion of a scene from Ingmar Bergman’s “Scenes from a Marriage,” waking in tears after a nightmare. Near the end of “Scenes”, the Liv Ullmann character wakes after a nightmare in horror and tears and says, clinging to her ex-husband,

“Are we living in total confusion? All of us? Do you think that secretly we're afraid we're slipping downhill and don't know what to do? . . . Have we missed something important?"

But I did read a couple of books recently that I loved.4

Emily Witt’s Health and Safety: a breakdown was one. I had read another of Witt’s books, Future Sex, years ago, and it influenced me a great deal. Health and Safety is a book about rave culture and positive views of drug use but also about the political atmosphere of the past few years—it takes us through Trump’s first election, COVID lockdowns, and the protests of the summer of 2020. It is also about a woman trying to find a way to live outside of expectations and the breakdown of a romantic relationship. I ate it right up, though it is certainly not a book to make anyone feel less apocalyptic.

But for the previous five years I had tried to figure out how to live life outside of the kind of family I had grown up with. I had withstood the discomfort of changing my expectations. . . . A wedding now seemed like a dumb pageant. I watched my friends believe they could find protection and care in an institution that had given women the legal status of brood mares. Their belief that marriage had been modernized and reformed and that one could enter into it without becoming another person’s servant. . . . [Simone] de Beauvoir was one of the few women who had articulated her resistance to this false promise and who had done so with a determination to be happy. Even if it meant I would end up alone, even if it made my life more difficult, something in me resisted, too. I knew there would be a cost, but I could not believe the lie that if I mimicked the patriarchal model of family I would receive comfort and safety in exchange. That was the lie of fascism. I knew I would never be able to cosplay as a wife. Not after all that learning.

I will say that I do not find a wedding a dumb pageant—or maybe it’s that I like dumb pageants. Forever I’m Lydia Bennett saying “I long for a ball.” Anyway, I loved Health and Safety and would love to hear from anyone else who’s read it!

And, I finally, thankfully, found Eve Babitz. I had been told to read her by multiple friends and acquaintances and even one student, but found I had no urge to—I was sure she would have nothing for me, since I believed she was an LA type of cool girl I had no aspiration toward and no interest in. And then, probably because Babitz is in the air because of a recent release pitting her against (or at least putting her in contrast with) Joan Didion, a writer I’ve never especially loved, I read Slow Days, Fast Company: The World, The Flesh, and L.A.

And then I read it a second time. I was immediately rapt by her voice. I was laughing while I read. The greatest surprise to me reading this book was that I saw myself there, a surprise because I had been alienated by the facts I’d read beforehand and thought (perhaps out of that same class resentment referenced above) I’d be alienated by her. After all, I have never played naked chess with a Dadaist idol of 20th century art, I don’t have any godfathers at all, let alone famous composer ones, and I don’t even live in Los Angeles! I just live near enough to Los Angeles to sometimes go there!

A friend recently told me how strange it was that I was so extroverted and people-oriented but that I had made such introverted career choices—novelist and, now, librarian. And I told her, well, look at Eve Babitz! She’s so smart and reads all the time and her sentences are wonderful, but she loves to be among people. She loves an adventure. And she’s a romantic.

And everyone who writes about her seems to reference how she hasn’t been taken seriously. I recognized, too, that in my own desire to be a person who remains open to experience, a person of exuberance and romance, I might be mistaken for not being a serious enough mind as well. (I thought of a person of my acquaintance who often accuses me of performing things for the benefit of men, and then I’m lost wondering what it might mean to be charming without trying to charm). Even Slow Days, Fast Company is framed as an attempt to seduce a particular lover—look at this opening!:

This is a love story and I apologize; it was inadvertent. But I want it clearly understood from the start that I don’t expect it to turn out well.

I am at risk, in my enthusiasm, of quoting the whole book to you, so maybe just go read it. But what I was struck by, even more than her adventurous spirit, was the way this narrator seems capable of really loving people and having buckets of fun with them—her friends and her lovers and her acquaintances. It seems to me a lovingness and openness to others which reminded me of the spirit of Mrs. Dalloway and her “talent for friendship.” She’ll go to a baseball game on a lark because a lover wants to go and get so caught up that very quickly she’s like “omg do i love baseball???”

Well, I’m getting off track. Who cares. But here are some pertinent quotes to end on:

Women are prepared to suffer for love; it’s written into their birth certificates. Women are not prepared to have ‘everything,’ not success-type ‘everything. . . . There’s no precedent for women getting their own ‘everything’ and learning that it’s not the answer . . . . They’ll only give you ‘everything’ if you appear to be totally confused.

And:

She had always been conventional, that was what was so great about her. She was almost thirty. I had thought about it myself; getting married and calling it a day, but then, after San Francisco, I knew those songs of love were not for me. There was very little precedent for not getting married, I’ll admit…

Okay, and, lastly, a quote from Melissa Anderson’s Bookforum review of Lili Anolik’s previous biography of Babitz (will I still read Anolik? maybe…):

What Anolik appears to really love is the idea of Babitz. . . . . But that awe is disingenuous. Later, Anolik seems to pity Babitz for not being Anolik—that is, a wife, a mother, financially secure, ambitious. Never married, forgoing the conventional path Anolik has followed, mostly dormant since her accident, Eve is labeled “a child,” one who will never grow up: “She was beholden to nothing and no one—not a man or kids, or a piece of property, or a boss, not even to an audience. Adulthood was a condition she simply wouldn’t submit to, and that was that.”

This is narrow-minded, condescending, and sanctimonious. I doubt Babitz will care.

Another quote from Emily Witt’s Health and Safety, which I cannot fit into this overpacked thing: “I understood it was impossible for any writer to see outside the contours of the history they inhabited. I often thought about Edward Said’s explanation, that we still read Joseph Conrad in the twenty-first century, not because he had been capable of condemning racism and imperialism but because, as someone trapped within a totalizing ideological system in the 19th century, he had been a master of the only tools a writer has at his disposal when he suspects something is very wrong: observational detail, self-consciousness, unease, doubt.”

Ethically, what to do about one’s parenting and one’s children in writing about all this seems to me a conundrum.

Look, I didn’t even like Nightbitch.

Actually one great side effect of being on a new career track is that I am reading for pleasure again and have been reading indulgently.

Liz, every time I read your newsletter I finish wishing I could sit down for a big long conversation with you. In person and immediately. Thank you for putting these thoughts out there.

Love this, Liz. <3